Going global: does EU membership restrict trade with non-EU countries?

Being in the EU does not mean we cannot trade with non-EU countries. Germany exports more to the Commonwealth than we do. It is true that the majority of our exports go to non-EU countries but this is because the EU has used its status as a bloc of some 500 million people to negotiate a raft of advantageous trade deals with non-EU countries and we can take advantage of these as EU members. If we leave the EU, these deals will almost certainly no longer be available to us and we'd have to renegotiate with over 50 other countries who would be far less willing to give us, as a bloc of only 65 million people, the same good deals as the EU gets. This is before we think about other factors, such as the UK's lack of skilled trade negotiators and the fact that other potential trading partners such as Commonwealth countries no longer see the UK as a natural trading partner. Put simply, it defies common sense: why should other countries be interested in giving us better access to their markets once we leave the EU when we have few trade negotiators and we've given up the biggest incentive we have to offer in trade negotiations, namely full access to the European single market? The free movement of people, which was a major talking point of the Leave side in the referendum, is increasingly on the demand list for potential trading partners such as India and as a smaller entity than the EU, the UK on its own will find it harder to resist these demands as well as the demands made by other powerful coutries such as the United States. "Going global" to replace the EU market won't work because there isn't a wealth of untapped trade out there and even if there was, we would disrupt ourselves immensely trying to chase it. Before the referendum and her "road to Damascus" conversion to the Brexit cause Theresa May more or less admitted this. It isn't necessary to leave the EU in order to open up new markets to British companies.

In response to the economic evidence that leaving the EU single market and customs union would be highly damaging to the UK, supporters of leaving the EU claim that we can trade with the rest of the world instead. This is often stated in terms of "We're going global!", "We are global leaders in free trade" or "There are more than 27 other countries in the world!" There is a particular focus on trading with the Commonwealth as a substitute for the EU. However there are numerous problems with this approach.

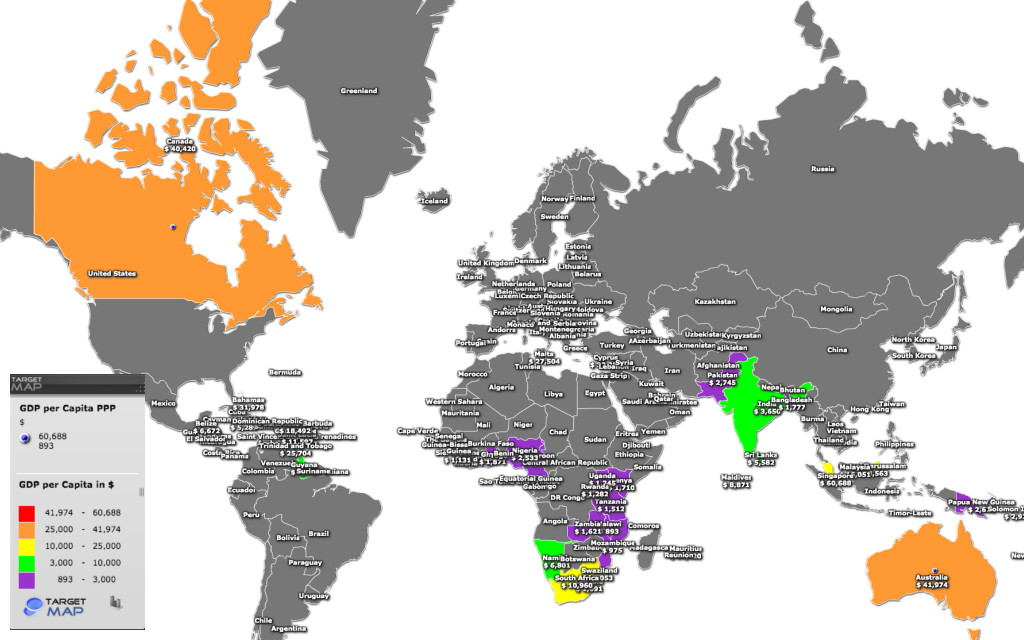

There are only a few wealthy countries in the world - and we already trade with them on good terms

Once we take Canada, Australia, India and South Africa out of the picture (the first three especially), the Commonwealth countries simply don't have that much money. Indeed, the same can be said for the rest of the world: there are a handul of wealthy, developed countries such as the US, Japan and South Korea and there are some rapidly-developing countries aspiring to join this club (China and India in particular). However outside the developed Western world, many countries don't have much money. Since the UK's exports are largely high value goods such as aerospace components, pharmaceuticals (developing countries such as India are lobbying hard to be allowed to make generic, cheaper versions of patented Western drugs, arguing that saving lives is more important than the profits of Western pharamceutical companies) and vehicles (but with the European market dominating exports, taking 56% of car production, the next largest being the US at 14.5% and the largest Commonwealth export destination being Australia with only 1.5% of UK car exports going there) the importance of reaching wealthy customers is clear.

Once we take Canada, Australia, India and South Africa out of the picture (the first three especially), the Commonwealth countries simply don't have that much money. Indeed, the same can be said for the rest of the world: there are a handul of wealthy, developed countries such as the US, Japan and South Korea and there are some rapidly-developing countries aspiring to join this club (China and India in particular). However outside the developed Western world, many countries don't have much money. Since the UK's exports are largely high value goods such as aerospace components, pharmaceuticals (developing countries such as India are lobbying hard to be allowed to make generic, cheaper versions of patented Western drugs, arguing that saving lives is more important than the profits of Western pharamceutical companies) and vehicles (but with the European market dominating exports, taking 56% of car production, the next largest being the US at 14.5% and the largest Commonwealth export destination being Australia with only 1.5% of UK car exports going there) the importance of reaching wealthy customers is clear.

Other UK exports are services, particularly financial services but also services such as education and legal work. Financial services exports to the EU totalled £22.7 billion in 2014, and financial services exports to the US alone were £21.6 billion in the same year. With this in mind however it's difficult to see how leaving the EU would improve on the figure for financial services exports to the rest of the world, or that it makes a case for "trading globally". If anything it reinforces the fundamental point that EU membership does not prevent us trading with the rest of the world - we have the best of all worlds in having a good trading relationship with a large number of affluent customers who are, in global terms, effectively on our doorstep, whilst at the same time reaching other  customers around the world.

customers around the world.

Distance matters: the "gravity" effect

All the points raised in this article so far don't take account of one very important effect: the economic law of gravity. Just as with, say, trying to bring two magnets together where we find that the magnetic attraction or repulsion is highly dependent on the distance between the magnets, so it is with international trade. Countries closer together tend to trade much more with each other than countries further apart. The reasons for this are not just social (that we share more common values and history with Ireland and the Netherlands than we do with say, Japan or Korea) but also practical. Transporting goods over large distances obviously has implications of time and cost, especially for perishable goods such as agricultural produce. Even where no transport costs are involved, as with for example selling your services to a remote customer, there are practical difficulties. How do you sell legal services to a customer on the west coast of the USA when only a few hours of your working days overlap? Ultimately, why should customers on the other side of the world want to purchase from the UK when they can usually find something much closer to home that suits their needs?

EU trade deals with non-EU countries

Much of the debate in the run-up to the referendum of the size of the EU market and our relationship with it. What

An excellent practical example of this is the EU-Japan trade agreement which was announced in July 2017. Alongside the usual features of a trade deal in terms of reduction of tariffs, there is a very important part of the deal that hasn't reached the headlines: Japan has agreed to open up its services and internal procurement market to the EU. This has been possible only because of the fact that the EU offers access to a market of 500 million people (including the UK) and being able to put this on the negotiating table extracts significant concessions from the other side in return. It's extremely unlikely that the UK, negotiating alone with Japan, could have obtained this concession because we can only offer access to a market of 65 million people. Those in favour of Brexit and who propose the idea of a "nimble", "global Britain" being able to access new markets more quickly than the EU, and who believe that the EU's trade negotiations are slowed down vastly by the need to accommodate the separate wishes of 28 member states and to translate official documents into different European languages, neglect to take account of the fact that it is size that really matters in trade deals. By very definition, the longer the negotiations the better the end deal will be: a series of "quick deals" as proposed by the "global Britain" lobby wouldn't be the best deal possible for the UK. The amount of time taken to accommodate the wishes of each individual EU member state and to translate the documents into different languages is small compared to the actual time taken to thrash out a good deal in the first place. Good trade deals take time to negotiate regardless of the size of the parties and we don't have time - since triggering Article 50 on 29th March 2017 we are on course to leave the EU (and thus access to its favourable trade deals) on 29th March 2019.

Trade in services: more difficult than trading goods

The deals negotiated by the EU often include services and this is important to us given that our economy is 75-80% services and financial services especially are one of our major exports to non-EU countries. However trade in services is more difficult to negotiate than trade in goods: the instinct of many governments is still to protect their service sectors for foreign competition whereas trade in goods can provide complementary products to satisfy consumer demand (in other words, country X produces A but not B and country Y produced B but not A, however both X and Y have companies providing services and they want to protect them from foreign competition). China is a good example of this but yet China would be high on the list of countries the UK might seek to do deals with, if we leave the EU. Trading services also requires other aspects which were given by the Leave campaign in the EU referendum as disadvantages of EU membership and reasons to leave:

- "Laws not made in this country" - if trading in services with another country, we would have to reach agreement with that other country on what is acceptable to that other country. For example, is a UK qualification in a given field such as law, education or telecoms engineering acceptable proof of a UK person's competence to perform tasks? Is a UK university degree of equal value to a degree obtained from an overseas university? This needs agreement at supra-national level, much like the EU single market does.

- "Unlimited immigration" - financial services are one of the UK's biggest exports to non-EU countries and some can be handled remotely, such as insurance or banking. However other services that we might seek to provide to overseas customers such as education, design and engineering, tourism, architectural work and surveying, all require the seller of services to be able to meet the customer for those services. It would be incredibly cumbersome to have to deal with visa requirements for work as opposed to say, study or tourism, when attempting to arrange for a provider of services to visit his overseas client and as such selling many services effectively requires freedom of movement. Restrictions on immigration are harmful to the UK university education sector, but university education is one of the things we sell that is of great interest to overseas countries. Put simply, we can't sell our education services to people who are not allowed to come to our country to study. Freedom of movement is a two-way street thst benefits the UK as well since it allows our talented professionals to sell their services abroad and we will return to this theme in another article on this site.

The National Institute of Social and Economic Research has produced a useful video summarising why the EU single market or an equivalent setup is essential to successfully trading in services.

Other potential non-EU markets we might seek to tap into are:

- The USA - but we already have a healthy trade surplus of £28 billion (on average, for the period 2005 to 2015) with the US. This is without having a free trade deal, either at UK or EU level, with the US. Concern was expressed over the proposed EU-US TTIP deal but it is difficult to see how the UK could avoid many of the worst aspects of TTIP because we are far smaller negotiating partners than the EU, compared to the size of the US. It's difficult to imagine how we, the UK, could avoid putting market sectors up for grabs to US companies that the UK public cherishes greatly (think: US companies being able to buy into a part-privatised NHS) and also, given that tariffs on trade between the UK and US are already quite low at 3% on average, any real gains from a UK-US trade deal would come from even more contentious issues such as food safety standards (the US permits hormone-raised beef and bleached chicken meat which the EU, and by extension the UK at present, does not). Both the UK and US have well-developed financial services sectors but for UK firms to make real progress in the US market we'd have to agree to US rules as the relative size of the US compared to the UK means it's highly unlikely that the US would be happy to change its rules to accommodate the UK's preferences - and yet one of the major planks of the Leave campagin was that we would "take back control" and no longer be subject to "laws not made in this country". In short, some well-qualified commentators believe that a UK-US trade deal wouldn't achieve that much, especially not without major concessions that either side would find a difficult political sell to their electorates.

- China - there are concerns about whether China is truly a market economy, particularly in light of allegations that it has been "dumping" unfairly cheap steel onto the world market - that is to say, is it fully fair and competitive or are there unseen factors and influences such as state support for industry behind the scenes? If we enter negotiations with China, are we playing a truly fair game or does one partner have cards stuffed up their sleeves? Aside from these concerns, the fact remains that China is some five times bigger than the UK, and bigger players set the tone for negotiations (for obvious reasons). It's worth looking at the Switzerland-China trade deal which was concluded in 2013. This deal is heavily skewed in China's favour which is what logically you would expect given that China is much the bigger partner and as a result, Switzerland needs China much more than China needs Switzerland. From the agreement we see that "While Switzerland will dismantle import duties on almost all (99.7%) products originating from China from day one of the entry into force of the FTA, with only very few reservations for agricultural products where tariffs will remain, Chinese import-taxes on most (96.5%) Swiss products will (merely) be reduced gradually within rather long transition periods ranging from 5 up to 15 years." It's also worth noting that "In 2013, Swiss exports to China amounted to approx. CHF 8,8 billion (i.e., only 3.7% of all Swiss exports)..." (by way of comparison, in 2013, China accounted for 3.6% of UK exports). There are serious concerns regarding selling "hi-tech" products or services into China because the procedures for proving that the things we seek to import into China will meet Chinese standards are decidedly non-transparent: the major concern is that this is deliberately done either to allow China to claim "home advantage" for its own companies (by shifting the goalposts if it deems this convenient) or "the requirement to disclose sensitive technical know-how and trade secrets to the competent [Chinese] authorities". In short, China is something of a dangerous game: it may be possible for UK companies to win but the rules of the game are unclear and there are constant suspicions that the home side is cheating.

- Ethically dubious sales of arms to oppressive regimes have also featured recently as UK representatives have toured the world seeking to drum up trade that might replace the EU if we leave. There has been some concern at a visit by Liam Fox to the Phillipines and Fox's talk of "shared values" with the president of that country, Rodrigo Duterte who is considered "out of favour" in many international circles because of his approach to the country's drugs problem. It gives the impression of desparation on our part and all for deals that, even if they resulted in ten-fold or more increases in our exports to these countries, could only represent fractions of the trade we would lose by leaving the EU.

In short, "going global" is a scenario with far more problems than genuine prospects for improvement. Politically speaking, the few wealthy Commonwealth countries don't want what we've got to sell or have formed stronger trading relations with their neighbours since the end of the British Empire (or both), many other countries in the world don't have the means to afford what we would sell even if they did want to buy it, other wealthy countries are either already tapped into by EU-level trade deals or have protected markets which even the EU at many times our size and influence struggles to break into and, ultimately, they are all too far away to make it possible to achieve significant increases in our export sales to them. There is no subsitute for the large, affluent market of 450 million or more customers that's right on our doorstep and is called the EU single market - even though we are determined to jettison these ideal customers for our products and services. Indeed, a leaked report from the UK Government Treasury concluded that the cost of seeking out non-EU trade deals if we left the EU, wouldn't be worth it in terms of the extra trade generated. Other independent economic researchers have reached similar conclusions. As Theresa May put it before the referendum:

“We export more to Ireland than we do to China, almost twice as much to Belgium as we do to India, and nearly three times as much to Sweden as we do Brazil. It Is not just realistic to think we could just replace European trade with these new markets.

But in a stand-off between Britain and the EU, 44% of our exports is more important to us than 8% of the EU’s exports is to them.

Remaining inside the European Union does make us more secure, it does make us more prosperous and it does make us more influential beyond our shores.

I believe it is clearly in our national interest to remain a member of the European Union.”

Theresa May, April 2016.

By way of a parting analogy, let's ask ourselves: why does the Earth orbit the Sun? The answer is that the Sun is by far the largest and most influential body in our section of the Universe; influence in this case being its gravitational pull. The Earth is captured by the Sun's gravity and orbits in an ideal position - not too hot and not too cold, but just right to support life. In theory, we could equip our planet with an absolutely enormous propulsion unit to blast it free of the Sun's gravity and take the Earth out to "explore the Universe" where after all, there are "thousands of other planets out there!" However we need to consider that the effort required is so huge as to be almost impossible, secondly that we'd be very unlikely to survive the journey away from the warmth of the Sun and after all that, what point is there to the exercise anyway since we have no idea if any of these thousands of other planets are actually inhabited by intelligent life with which we could communicate. So it is with pulling the UK out of the EU market to "go global" - we are almost ideally positioned where we are, it would require an immense amount of effort which would without any doubt whatsoever bring about massive economic (and as a result, social) upheavals and at the end of the day isn't worth it because there's nothing to be gained. Keep this argument handy next time you hear someone wax lyrical about "going global!"